21st Century Crimes Against Humanity: Oppression of the Uyghurs in China

A demonstrator wearing a mask painted with the colors of the flag of East Turkestan—how some separatist Uyghurs refer to the region of Xinjiang—and a hand bearing the colors of the Chinese flag, attends a protest denouncing China's treatment of ethnic Uyghur Muslims, in front of the Chinese consulate in Istanbul, on July 5, 2018. Source.

If you have paid attention to news or social media over the last six months, you have likely heard of the Uyghur (pronunciation: WEE-gurr) ethnic group of Northern China. Maybe you saw a series of Instagram posts on a friend’s story, or saw #saveuyghur trending. When Mulan was released in September 2020, perhaps you saw headlines criticizing Disney for shooting in Xinjiang and thanking its security bureau. You might have read an article about human rights abuses in which the Uyghur detention camps were mentioned. But one basic question still evades most North Americans when asked: who exactly are the Uyghurs? Why is their current plight being compared to Rwanda, Myanmar, or the Holocaust?

A Brief History

The Xinjiang Autonomous Region is a vast, rugged territory in Western China, rich in natural resources, and bordered by 8 countries: Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan (via the contested Kashmir region), Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia. It has long been of strategic and economic importance dating back to the famed Silk Road that connected Asia and Europe through this territory. Today, Xinjiang is populated by more than 40 ethnic groups, the largest of which are the Uyghurs. Estimates vary, but most agree that the Uyghur population is around 11 million people. They are a predominately Muslim, Turkish speaking ethnic minority like the Central Asian countries they border.

Xinjiang Autonomous Region in China. Source.

Xinjiang has been subjected to attempts to control and incorporate since the Han dynasty sought to bring the Silk Road under their control beginning in 200 BCE. Various invaders like Genghis Khan in the 13th century and dynasties such as the Qing from the 17th-20th century would compete with local tribes for control of the territory. However, the current conflict stems, in part, from an independence movement in the mid 20th century that led to the creation of two partially recognized states in what is now Xinjiang: the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan in 1933-1934 and the East Turkestan Republic from 1944-1949.

The first expression of the modern Uyghur independence movement was the foundation of the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan. The Nationalist government of China at the time began to crack down and attempt to “unit[e] all minority nationalities with the Han,” denying the right to national self-determination for ethnic minorities. In November 1933, the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan was founded in defiance of this Sinocentric view that tried to assimilate them into the dominant Han Chinese culture. However, the Soviet Union, anxious about self-determination and rebellion expanding into the territories they controlled, collaborated with Nationalist Chinese government to militarily subdue the republic in 1934, after just six months of its existence.

Ten years later, in the wake of World War II, the East Turkestan Republic revived the hope of Uyghur self-determination. With the Soviet Union secretly backing their endeavor, the independence movement established a new republic in 1944. However, the Soviet Union used their support of the East Turkestan Republic to gain leverage against the Chinese in post-World War II conferences and later on in negotiations with Mao Zedong after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) defeated the Nationalists in 1949. Despite political differences, the CCP retained their belief in an “irresistible and inevitable trend, namely, the trend toward a united people's China,” in which minority nationalities were assimilated. Again with the help of the Soviet Union, the government of China invaded and subdued the East Turkestan Republic on 22 December 1949. The current oppression, violence, and ethnic tension in Xinjiang unfold against the backdrop of centuries of contested dominion and ethnic freedom.

Xinjiang in 21st Century Global Politics

While the framing of the “Xinjiang problem” has changed, the basic posture of the CCP has not. Throughout the first fifty years of the People’s Republic of China, the CCP justified its actions in the language of separatism and national unity. In the post-World War II era, where self-determination was a paramount Western ideal, Chinese action toward Xinjiang was criticized by the United States and the West. However, after the 9/11 attacks shifted the world’s focus to Islamic terrorism, the CCP changed its language, describing its actions in Xinjiang as part of the struggle to eliminate extremism. Beijing also offered Western armies assistance in Afghanistan against Al Qaeda in exchange for silence on the Xinjiang issue. Ethnic conflict and violent terrorist attacks in Xinjiang in 2009 and 2014 crystalized these fears and helped the CCP justify its repression. Xinhuanet, the official newspaper of the CCP, continues to use the language of extremism and anti-terrorism when denying claims of human rights abuses. As the United States pulls out of the Middle East and conflicts with China increases, the Uyghur oppression has come back into the spotlight.

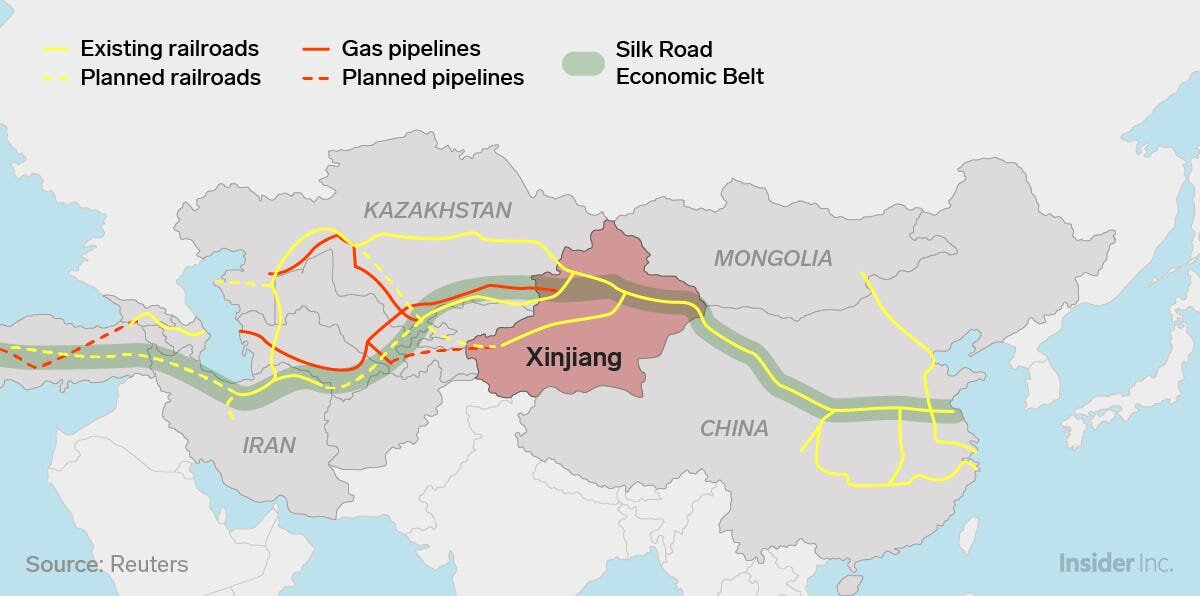

The announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the strategic importance of Xinjiang have led to increased oppression in Xinjiang. The BRI, or “One Belt, One Road” program, was announced in 2013. It is President Xi Jinping’s vision of recreating the Silk Road and reasserting Chinese political and economic power globally. The “Road” is a maritime route from the eastern seaboard of China to Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe. Plans for the “Road” have increased tensions, particularly in the South China Sea. The “Belt” is a land route from China into the Middle East and Europe, recreating the old Silk Road which runs right through Xinjiang (see image below). Given U.S. naval superiority, the “Belt” is a key means of assuring Chinese access to oil and gas in the Middle East without U.S. interference. Furthermore, Xinjiang itself has large oil reserves (20% of China’s total) and large coal reserves (40% of China’s total). Therefore, control of this region is vital for China’s economic strategy to succeed, especially in light of increased U.S. scrutiny and pressure on China

Proposed map of the “One Belt One Road” program. Source.

Uyghur Oppression in Modern Xinjiang

Xinjiang has all of the hallmarks of a police state. In 2017, Xinjiang accounted for 20% of the country's arrests, despite housing only 1.5% of the population. GPS tracking devices are mandated on vehicles, facial recognition cameras have been installed on mosques, and to obtain a passport, residents of Xinjiang must submit DNA samples, voice samples, a 3D image of themselves, and their fingerprints. The CCP has long encouraged Han to migrate to Xinjiang to dilute the Uyghur population. In 1949, when the CCP took over, Xinjiang was 5% Han and 75% Uyghur, by 2010 Xinjiang was 40.5% Han and 46% Uyghur.

Direct evidence of intentional ethnic cleansing has been hard to locate due to Beijing’s secrecy, but the security wall broke earlier this year. The “Karakax List,” a document leaked from Beijing in January and named after Karakax county in Xinjiang, details the reasons for the internment of around 300 Uyghur individuals. The most common reason listed was a violation of family planning practices that place limitations on the number of children ethnic minorities can have. Uyghurs face employment discrimination and are denied jobs in certain sectors. Disturbingly, as part of the “Becoming Family” program, Chinese officials will conduct homestays where they spend five days every two months in different, primarily Uyghur homes, to collect information, monitor behavior (such as religious practices), and promote CCP beliefs by teaching Mandarin and political ideology.

Beyond these abuses, the U.S. divides the most horrific human rights violations in Xinjiang into three broad categories: forced sterilization, forced labor, and violations of religious freedom. These systematic violations have led to the arbitrary arrest of one million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities for detention in what the CCP calls vocational education and training centers beginning in 2017. Leaked drone footage from Xinjiang of men being carted on trains to the detention centers, with heads shaved and hands bound, added to the growing body of evidence of repression and abuse in these internment camps. While other minorities, such as ethnic Kazakhs, are also subject to these persecutions, they are primarily targeted toward the Uyghur due to their tumultuous history of resistance and ethnic and religious differences from the rest of China.

Forced Sterilization

Officials from the Family Planning Committee in Xinjiang released a notice in 2017 mandating that women who had exceeded the limits on children “both adopt birth control measures with long-term effectiveness and be subjected to vocational skills education and training.” One local government explicitly stated their goal was to “guide the masses of farmers and herdsmen to spontaneously carry out family planning sterilization surgery, implement the free policy of birth control surgery, effectively promote family planning work, and effectively control excessive population growth.” Xinjiang officials budgeted 37 million dollars towards these health care goals, the sterilization rate skyrocketed, and the birth rate fell dramatically, perhaps in part due to the threat of internment if the women refused. Former detainees report being forced to have abortions, IUD implantations, and/or be sterilized while attending classes about the proper number of children.

Forced Labor

Beyond the one million Uyghur and other ethnic minorities in internment camps, some estimate that over 80,000 Uyghurs have been sent around the country performing a variety of factory and agriculture jobs. The “Xinjiang Aid” program was publicly portrayed as a program to give work and contribute to poverty alleviation, even before the uptick in detentions in 2017. Beyond the labor, they are forced to take Mandarin, subject to ideological indoctrination, and are prohibited from practicing their religion.

In 2020, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection has issued eight withhold release orders of Chinese which flag companies that have significant, but not conclusive, allegations of using prison or forced labor. The U.S. is considering further, broader restrictions on the importation of cotton and tomatoes from Xinjiang. On September 22, 2020, the bipartisan Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives and headed to the Senate for consideration. The bill would prohibit all goods made in Xinjiang or through programs that under the guise of “poverty alleviation” subject Uyghurs to forced labor unless there is clear evidence that the process was free of forced labor.

Violations of Religious Freedom

The second most common reason listed for detainment on the Karakax list is for practicing Islam. The list of extremist behaviors includes growing a beard and wearing a headscarf. Praying, studying, or simple possession of the Quran are also in violation of regulations, and one man was sentenced to 10 years in prison for “inciting extremist thoughts,” for the crime of inviting a coworker to pray. Fasting or closing restaurants during Ramadan is also prohibited. Abdulsalam Mohammed, an Uyghur who fled Xinjiang to Australia after being detained, described his experience in the internment camp: “The 10 hours of class they would teach one day were the exact same 10 hours they'd teach the next. The goal was to change our minds, our faith, our beliefs. It was a plot to force us to renounce our religion.”

One particular row on the leaked Karakax list stands out. The rationale for entry number 10, evidently a young man whose family had been detained previously, is as follows: “This person has quite a lot of family who have been detained or sent to training. The family is deeply religious. They are young and have not gone through compulsory education.” Simply having a religious family that had been detained for religious reasons was enough to send this person along with them, despite the fact he had not done anything himself. Vilifying and demonizing the Uyghur faith violates part of the core of their identity and represents an attempt to strip away their sense of self, community, and history.

The list of abuses in the Xinjiang region committed against this historically resilient group is ever-growing. Forced sterilization, constant surveillance, forced labor, violations of religious freedom, political indoctrination, and baseless imprisonment has led many prominent think tanks and human rights organizations to call on the United Nations to launch a genocide and/or crimes against humanity investigation. Next time you see a news article describing new information, or an Instagram story drawing attention to these abuses, do not just glance at it. Remember that this is a culturally rich region with a deep history, and that an ideological-economic power struggle is carried out each and every day that is destroying millions of lives.