Foreign Aid: An Ever-Failing Yet Highly Valuable Quest

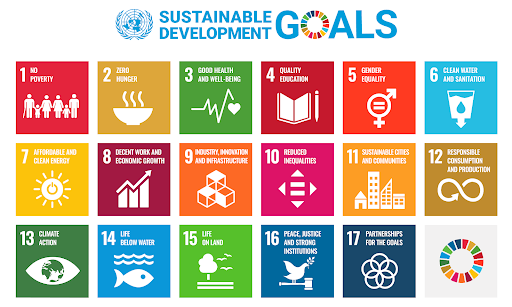

17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Source: United Nations.

A decade ago, the United Nations (UN) unanimously adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), ambitiously aimed at bringing “peace and prosperity for people and the planet.” Elevating aspirations even further, the UN sought to complete the Agenda for Sustainable Development by 2030. Five years from this deadline, the prospect of achieving these goals looks bleak.

As of September 2025, only 18% of the goals are on target, more than half lag behind, and around a fifth have even regressed, those being: Poverty reduction (SDG 1) as the World Bank’s higher $3-a-day threshold leaves 125 million more people below the poverty line, quality education (SDG 4) with 272 million children out of school, and progress on climate action (SDG 13) and strong institutions (SDG 16) likewise faltering. Reasons for falling back on the SDG goals are manifold but largely traceable to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and a growing withdrawal from foreign aid commitments by key donor states.

The American-led modern state aid project can be traced back to President Truman who in 1945 requested the Congress to offer aid to ‘preserve and free people’ against the political integrity of democratic nations, such as Greece and Turkey, against communism. The US provided $400,000,000 aid for Greece and Turkey. Separately, the US Congress approved the Marshall Plan to reconstruct Europe from the ruins of World War II with $13.3 billion aid assistance. Since then, foreign aid has provided for American foreign policy, diplomacy, development, and defence.

The following decades saw the creation of international institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Their creation coincided with a period of decolonization in which dozens of new states in Asia and Africa gained independence. Under the guise of promoting democratic freedom and development, however, a new division emerged: the Global North, seen as progressive and developed, and the Global South, portrayed as backward and in need of rescue. This divide is also notable in the “success” of the UN. Top-donor countries, such as the United States and wealthy European countries, have not experienced war since the creation of the UN and, until the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war, could indeed ensure peace for certain.

Meanwhile, foreign aid remains a lifeline for many countries in the Global South that rely on external help to cover basic human needs such as clean water, food, and healthcare, and are often subject to violent conflict. Sarah Bermeo of Duke University highlights how aid and development are overlapping but distinct fields. While aid is publicly justified as promoting development, it has often become a foreign policy tool serving donors’ strategic interests. Development outcomes can easily be sidelined, as evidenced by the recent closure of USAID missions and a projected decline in foreign aid commitments among OECD countries by 9-17% in 2025 alone.

As a Rotary Peace Fellow, I am particularly concerned about the impact of these cuts on peace-making missions worldwide. The Stockholm International Research Institute reports that peacekeeping deployments fell by more than 40% between 2015 and 2024 due to funding shortfalls. Considering these worrying trends, it is easy to grow cynical and dismiss foreign aid as a failed enterprise. Yet leading figures in the field urge otherwise.

I recently attended the 2025 Michael Sherraden Lecture at UNC, where Arjan de Haan noted that even seemingly unachievable goals act as focal points that mobilise resources and strengthen advocacy. Many scholars and practitioners see the current funding crisis not only as a setback but as an opportunity to reimagine aid, by doing more with less, rebuilding better, and diversifying donors. I applaud ongoing reform efforts, but donor countries and aid institutions must go further.

First, states should take responsibility for defining the purpose of aid beyond foreign policy interests. Strategies must clearly distinguish between short- and long-term goals and commit to following through. This would foster sustainable models that advance the SDGs and protect communities from being abandoned mid-project.

Second, the notion of “aid as a white man’s burden”, described by development scholar William Easterly, must give way to a model of agency in which donors and local recipients act equally in dialogue. Stated more bluntly, the practice of “white saviourism” has to be put to rest and the smokescreen of an altruistic model of foreign aid needs to be lifted. The prevailing top-down approach, which is driven by state self-interest, must change into a localized, bottom-up dynamic that empowers communities to decide where aid can make the greatest difference.

Third, foreign aid will always risk falling short precisely because it dares to aim high. Its very purpose lies in setting ambitious goals that draw attention and resources to challenges otherwise left unaddressed. Failure, therefore, is not evidence of futility but a by-product of striving for transformation in an unequal world.

Despite its imperfections, foreign aid remains one of humanity’s most meaningful collective actions against the ills in the world. Aid saves lives, fosters progress, and embodies a belief in shared responsibility. Rather than abandoning it, we must reimagine it so that aid becomes not an instrument of power, in a partnership grounded in fairness, agency, dignity, and the pursuit of a more peaceful world.