The Illusion of Intimacy: Parasocial Relationships in Modern Politics

Source: UGA Today

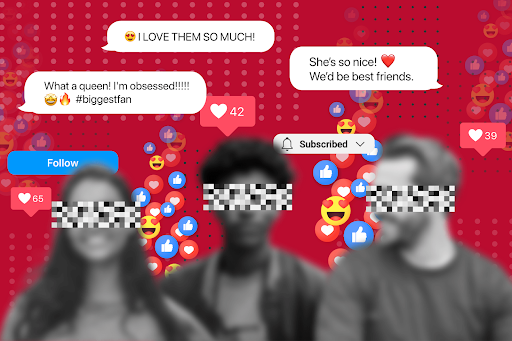

In digital politics, connection is currency—and some connections matter more than others. Politicians operate like nodes in a network, gaining influence not by what they do, but by how many people trust them. That trust clusters. It reinforces itself. It builds loyalty and silences dissent. Enter the parasocial relationship: a one-sided emotional attachment that makes followers feel personally connected to a public figure, even when that closeness is entirely constructed. In the age of curated feeds and crafted tweets, that emotional bond doesn’t need policy to hold, it just needs to feel real. The illusion of intimacy creates a feedback loop: loyalty replaces critique, branding replaces leadership, and power hides behind personality.

Because a politician’s greatest weapon isn’t policy—it’s your trust.

That trust becomes something harder to break. It creates a kind of cult loyalty, where criticism is no longer processed as critique; it’s treated as betrayal. The political figure becomes more than a leader; they become a symbol, and protecting that symbol becomes personal. As emotional allegiance grows, loyalty shifts from ideology to identity. Politicians no longer need to persuade or perform, they just need to be believed. The result is a political environment where branding replaces governance, and performance stands in for substance. This kind of loyalty doesn’t just deepen polarization, it narrows the space for dissent, suppresses contradictory information, and isolates followers inside a feedback loop.

This distortion has consequences beyond one figure. When perception carries more weight than proof, political engagement becomes reactive and defensive. Studies show that voters with strong emotional ties to political figures are more likely to reject opposing information and interpret fact-checking as an attack. That illusion of connection makes misinformation easier to believe and harder to correct. Leadership becomes an image to defend. Voters become an audience to mobilize. And politics becomes a closed circuit of belief, loyalty, and performance.

This relationship between politician and supporter is not abstract, it’s observable, and it’s organized. Nowhere is it more visible than in the rise of MAGA. Donald Trump did not enter politics as a policy figure, he entered as a persona, one familiar to millions through television and tabloid spectacle. Trump’s media presence created a parasocial foundation long before he campaigned. He appeared powerful, decisive, untouchable. And so when he moved to politics, the perception followed him. His political communication strategy reinforces that image through performance. Twitter becomes a tool for personal maintenance, and rallies are staged as emotional theatre, not civic engagement. The role of the supporter shifts as well, no longer simply a voter, but part of the spectacle itself. Through repetition, spectacle, and targeted fear, Trump constructs a political identity that demands allegiance over understanding. Phrases like “America First,” “Fake News,” and “Build the Wall” are not designed to inform, but to provoke. This function as branded cues, they are familiar, immediate, and emotionally charged. The message is no longer about content, but reaction because once a belief makes the metric, accountability ceases to be the expectation.

This is where the danger becomes structural. When politicians are protected by emotional investment, accountability is no longer expected, let alone enforced. Voters begin defending personas rather than policy, and contradictions are absorbed rather than confronted. Studies from the Trump era demonstrate that emotionally bonded supporters often dismissed evidence that challenged his claims, not because the facts lacked credibility, but because belief had already taken precedence. This means political allegiance becomes increasingly tied to affect, rather than analysis. This is due in part to the nature of parasocial bonds, which personalize the political and shift trust from institutions to individuals. As those bonds intensify, the political figure is no longer perceived as a representative, but as a reflection, someone who embodies rather than challenges the identity of their base. This means critique is interpreted as threat, and performance takes precedence over governance. When looking at the political landscape shaped by this dynamic, what emerges is not simply polarization, but a redefinition of democratic engagement itself.

Trump may be the clearest example, but he is not the exception: The conditions that enabled his rise such as emotional politics, media performance, and affective loyalty are not unique to him or to one party. They reflect a system where legitimacy is measured by recognition rather than accountability. Parasocial dynamics do not just distort how voters see their leader, they reshape what the public expects from politics itself. So when governance is reduced to performance and power is protected by projection, the cost is not just polarization, it is the quiet erosion of democracy.