Texas’s Blocked Map and the Growing National Fight Over Redistricting

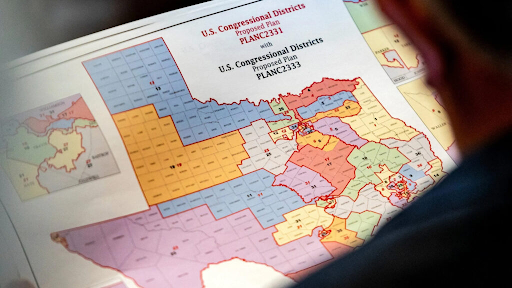

State Rep. Matt Morgan examines a map of the proposed congressional districts in Texas. Source: Reuters.

The 2025 off-year elections were an abrupt awakening for President Donald Trump and the Republican Party. Across the country, Republicans around the United States are rapidly losing support among several voters. Meanwhile, Democrats have seen a steady rise in favorability compared to Republicans, even as 45 percent of Americans continue to reject identification with either major party. This trend has been stable in the past few months. A November 2025 PBS News/NPR/Marist poll found that 55% of registered voters would elect a Democratic candidate to represent them in Congress if they had to choose today, compared to 41% who would vote for a Republican. This 14-point advantage is the widest gap since November 2017, just one year before Democrats flipped more than 40 seats in the House of Representatives. The all-around Democratic sweep across the nation has intensified requests from the White House to state governments to redistrict and secure more Republican seats in the House. Currently, Republicans hold a slim majority and can only afford to lose two seats nationally. Three GOP-controlled states, Missouri, North Carolina, and Texas, have listened and redrawn their maps ahead of the 2026 midterms, but Texas has now encountered an unexpected setback.

Texas Map Blocked

On November 18th, in a 2-1 decision, federal judges in El Paso blocked Texas's redrawn electoral map. Notably, the opinion blocking the new map was authored by Judge Jeffrey Brown, a Trump appointee, who found substantial evidence suggesting that the 2025 districts may constitute racial gerrymandering. The new map proposed would increase Republican-controlled districts from 25 to 30, while also eliminating five of the state’s nine coalition districts. The map also redrew districts so six Democratic incumbents would have to run against other incumbents, with five of those lawmakers being of Black or Hispanic heritage.

The federal court subsequently issued a preliminary injunction preventing the map’s implementation. Although a conservative judge ruling to prevent redistricting that favors their party seems counterintuitive, it’s not as shocking as one might assume. Historically, both conservative and liberal judges have been known to restrict racial gerrymandering. Racial gerrymandering, or drawing electoral district maps using race, is considered justiciable under federal law, reinforced by the 1993 landmark case Shaw v. Reno, which established racial gerrymandering as a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Exception to Racial Gerrymandering

At the same time, though, federal law recognizes circumstances in which race must be considered. Under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), courts are required to strike down maps that dilute the voting power of minorities. The VRA protects against any qualification or prerequisite to voting that results “in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color…” To justify using race in gerrymandering, a state must meet the Thornburg v. Gingles test, which requires proving 1) geographic compactness of the minority group, 2) political cohesion of the minority group, and 3) that the majority group acts as a block for the minority group’s preferred candidates. With these well-established legal doctrines, conservative judges have struck down Republican-favored maps when the evidence shows the lines likely targeted minority voters. In 2023, Judge Jeffrey Brown also ruled against another redistricting plan in Galveston County, Texas, after Attorney General Merrick B. Garland argued it “deprived the county’s Black and Latino voters of an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and elect a candidate of their choice.” Additionally, in the ruling of Allen v. Milligan in 2022, conservative Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh joined the three liberal judges in a 5-4 decision for Milligan that Alabama’s 2021 redistricting plan violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Why Partisan Gerrymandering Escapes Judicial Review

Unlike racial gerrymandering, however, partisan gerrymandering, or districting based solely on party advantage, is not managed by the courts. Rucho v. Common Cause, a landmark decision in 2019, ruled that partisan gerrymandering was a nonjusticiable political question outside of the court’s jurisdiction, meaning it falls outside the court’s authority and therefore cannot be ruled on. Essentially, the court ruled in a 5-4 decision for Rucho that concerns surrounding partisan gerrymandering cannot be heard as there is no clear standard or threshold in the Constitution or any living law for what is considered “too partisan.” Consequently, Trump-appointed and other conservative Republican judges take advantage of this decision and often apply this precedent broadly. This has led them to uphold numerous Republican-favored maps when the justification is framed as ‘partisan advantage’ rather than racial discrimination.

For instance, a three-judge federal panel in North Carolina recently allowed the state’s newly redrawn congressional map to take effect for the 2026 midterm elections, unanimously siding with Republican legislators after they argued that partisan motives rather than racial considerations shaped the map. A similar pattern is unfolding in Texas, where Governor Abbott has rejected allegations of racial gerrymandering and has instead defended the state’s new map as an effort to “better reflect Texans' conservative voting preferences.”

Rucho has significantly narrowed the Voting Rights Act’s practical reach by removing federal oversight of partisan gerrymandering, giving states far more freedom to draw maps without judicial review. This shift has had measurable consequences. According to a statistical analysis from Common Cause’s CHARGE Redistricting Report Card, states that engaged in aggressive partisan gerrymandering in the 2010 cycle (such as Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, and Wisconsin ) produced even more extreme gerrymanders in the 2020 cycle. The trend across these states shows how the absence of judicial limits has intensified partisan map-drawing, ultimately contributing to the predicament seen today.

Supreme Court Appeal

In response to the injunction from the federal court, Texas Governor Greg Abbott immediately appealed the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. Presently, the court is already hearing arguments for another major redistricting case: Louisiana v. Calliais. This case challenges the creation of a second majority-minority district (originally made to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act) because it violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments for being “race-based.” Whereas the current precedent, Allen v. Milligan, supports the creation of majority-minority districts, several justices have recently appeared skeptical of the provision, citing the relevance of Section 2 in the current day. Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh raised doubts surrounding Section 2’s longevity, saying, “race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time…but that they should not be indefinite and should have an endpoint.” If the Court rules in favor of Callais, Section 2’s protections could be significantly weakened or even overturned. While the Supreme Court typically issues major rulings by late June or early July, there is a chance the court may expedite the decision to rule on the recent Texas case and meet multiple states’ redistricting deadlines before the 2026 midterms.

Section 2: A Crucial Safeguard at Risk

Even as partisan gerrymandering only involves party differences, race inevitably becomes intertwined, as racial groups often vote cohesively for one party. Black-American voters, for example, have long been the stronghold of the Democratic Party and have consistently voted Democrat since the New Deal coalition. In the 2024 election, 86% of Black-Americans voted for Kamala Harris (D) compared to 13% who voted for Donald Trump (R). Therefore, even when gerrymandering is framed as party-based, it can still diminish the voting power of minority groups, particularly those of Black Americans. This is evident in North Carolina, where Congressional District 1, a historic Black Belt district in eastern North Carolina, was redrawn to reduce the Black voting-age population by more than 8%, and similar trends are now appearing in Texas.

Section 2 has long protected minority votes from this threat of voter dilution, and remains essential for safeguarding them in the future. A weakening of the Voting Rights Act, whether through Louisiana v. Callias or a future case brought by Texas, could enable multiple states to redraw their maps in ways that favor solely Republican candidates at the expense of votes from historically underrepresented groups. There have already been multiple attacks in court on the Voting Rights Act, one of the most prominent being the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, where Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act was considered unconstitutional and outdated. Following the decision, multiple states enacted new voting laws that imposed multiple voting restrictions disproportionately affecting voters of color. Further, there are around 30 more lawsuits pending that target Section 2 of the VRA specifically. If any of these cases prove successful, the Black Voters Matter Fund has found that 27 U.S. House seats for Republicans will be added, with 19 as a result of the loss of Section 2.

The ruling issued by Justice Jeffrey Brown and Governor Abbott’s immediate appeal to the Supreme Court highlight the increasing threats facing the Voting Rights Act. The ongoing redistricting battles have also spread beyond Republican-led states. Democratic-controlled states such as California, Illinois, and Virginia have begun proposing their own redraws to counter each of the seats Republicans gain from gerrymandering. The most notable of these is Proposition 50, which was recently passed by California voters, to add 5 more seats to the Democratic Party in the House. As both parties escalate their map-drawing strategies to outmaneuver one another, American democracy risks devolving into a redistricting “arms race,” undermining the system of fair and equal representation that the United States was intended to uphold.